Writer: Julian Shrike

Subject: THE DEATH OF VICTOR FRANKENSTEIN

Art by: @mobiusvast

Link: Tumblr / 21.07.2021 / The Death of Victor Frankenstein, a short story

Link2: Reposted by longwander

The Death of Victor Frankenstein

Before he made a name for himself building men out of corpses, Victor Frankenstein studied alchemy. Twelve years after his greatest failure, a visit from a man who would dare the unthinkable forces Frankenstein to embark on an experiment far madder than any Frankenstein has ever attempted before. The Death of Victor Frankenstein is a gay and trans take on the story of Frankenstein, inspired by horror movies of the 1930s.

It’s here! Yes, this is the Frankenstein story I’ve been promising. It’s 9k of repressed desires, magic, and mad science. The last sequence in particular I think is far and away the best thing I’ve ever written and has gotten a number of people to text me long strings of swearing.

ictor Frankenstein deserves no pity for what he made of himself. Oh, perhaps he weathered the cruelties of existence worse than some; still his total retreat from the world remained a luxury verging on self-abuse. In twelve years spent shut up in his manor, eating away at the remains of the family fortune, the most he achieved was to become rather old. It was merely a sort of general grayness. He was not yet old enough to be respected on age alone, nor for his failures to have faded from popular memory. There were many other things he could have done that would have wasted much less. For instance, he could have died.

Visitors were few enough that it was not unheard of for him to go nearly a year without seeing a single face beyond that of his one elderly servant, which suited him perfectly. The pleasures of the mind were far superior to any others, or so he told himself. After all, wine and good company did nothing to advance human potential, and what was a life of laughter next to one lived in pursuit of the deepest mysteries of existence? Not that Frankenstein had much to show for it. It was hard enough to admit to himself that he had abandoned unraveling the enigma of human life to spend his days mixing chemicals. If he had allowed himself to see that all he had done in the last decade was destroy a two-hundred year-old desk with acid stains, he might finally have cracked, and so that thought, like many others, was pushed down to the back of his mind, where it sat, festering.

The man called on him at ten o’clock in the evening. It was unusual to get any visitors at all, and that particular night was all howling wind and beating rain. From his vantage point in the sitting room, Frankenstein watched his manservant unlatch the door to reveal an odd, thin man. The man didn’t seem bothered in the least by the rain, in fact appeared with a smirk and a narrowed eye against a lightning flash, almost as if he had timed it for that. He was one of the strangest people Frankenstein had ever seen. While not particularly tall, he carried himself with a regal bearing. His face drew long, dramatic shadows in the dim light. On it he carried a waspish smile which suggested he thought himself above the rest of the proceedings, as if his arrival were a grand joke no one else was in on.

They were too far off to hear but the man greeted Frankenstein’s servant with a theatrical bow. The butler’s dislike was written in the tightness of his shoulders and his impatient grip on the door. If Frankenstein did nothing, it certainly wouldn’t be long before the door was slammed in the man’s face. He was right to do it, Frankenstein thought, since this was in all likelihood yet another person come to gawk and gossip at the famous madman. There had been altogether too many of them over the years, though they had slowed to a trickle by now. But Frankenstein had always let curiosity get the better of him.

“Let him in, Renaud,” Frankenstein called without rising from his easy chair.

The butler’s eyes darted to the door of the sitting room, though the gloom was nearly impenetrable from the brightly lit hall, aside from the soft orange glow of Frankenstein’s pipe. With a resigned raising of the brow, the butler stepped aside to allow the man access to the hall. The man passed into the manor with an upturning of the nose in the direction of the butler. Was it just the light that made it impossible to tell how old he was? There was something unstable in his face, as if caught in transition from one phase to the next. Something oddly familiar, too – had they met?

The sitting room was musty and overfull of centuries-old furniture. The dust had been there longer than Frankenstein himself. There was nothing to mark it as his space aside from the photograph he kept of poor Henry and a few odds and ends by the armchair, that being the only corner of the room that saw any use. Frankenstein had the distinct feeling he was being judged as the man’s gaze passed over the room.

The man gave a slight bow which somehow conveyed no respect at all. “Thank you for your hospitality, Baron. My name is Leopold Heron.”

And Frankenstein, grown gruff with solitude but still with the manners instilled in him from the moment he was born, said, “And what brings you all the way out here, Mr. Heron?”

Heron sniffed. “Doctor.”

“Doctor Heron, then.”

“I am here, Baron Frankenstein, because I am a scientist much like yourself. I am embarking on an endeavour with the potential to shift the course of human history, but I require the assistance of a skilled surgeon. You see, unfortunately I have suffered an injury which somewhat limits the use of my hands. You, I understand, used to be quite well known for your skill with a knife.”

Frankenstein drew slowly and at length from his pipe. He was used to snoops, of course. They may have been rare these days, most of them being young people pulled in while his story was still fresh, but they always started out with this sort of pretense. They were colleagues or students, researchers on some quixotic quest or another, who conspicuously avoided any mention of his famous blunder, as if dancing around his notoriety could fool Frankenstein into thinking he was still respected.

“That explains nothing, Dr. Heron,” he said, “I am regarded by most polite society as little better than a criminal. To come all the way out here is not an easy journey, and there are plenty of other surgeons. I’ll ask you again: why me?”

Dr. Heron laughed as if Frankenstein had said something funny. “Of course I am familiar with your work, of course. How could I not be?” and with a shrug, Dr. Heron sat delicately on one of the less dusty chairs. “I realize, of course, that you probably think what you did with your creature was unique – not without reason, I’ll grant. Unfortunately I must tell you that it wasn’t. Not at all. It was merely the most well-publicized experiment of its kind.”

“Doctor, I can assure you I have read all the relevant literature and if there were anything in it even tangentially related to my own work, I would certainly have heard of it. Now if you have nothing else for me, I think it’s best for you to go.”

Dr. Heron made no motion to leave, on the contrary he seemed to become increasingly comfortable. He tapped his lips with one long, graceful finger. Again Frankenstein felt that whisper of familiarity.

“Ah, but what if it weren’t in the literature?” he said, “The older methods tend to be much more secretive.”

“The older methods! I studied those too. They aren’t science and they aren’t medicine. They did me no good.”

“Then perhaps you simply studied the wrong texts. The works of Paracelsus -”

“Are a bunch of superstitious nonsense,” at which Dr. Heron looked almost affronted. “Now, Dr. Heron, if you have nothing more to show me then I’m afraid you’re wasting your time. I’m not an accessory for bringing a sense of the macabre to whatever it is you’re doing.”

Still Dr. Heron made no movement but to lean forward with a smile. “I’ve studied your methods as well, Victor Frankenstein. I’ve improved on them. Don’t think for a moment I chose you on a whim. Look at this.”

From his case Dr. Heron produced several envelopes full of documents. Crossing the room, he began to open them one by one, and with his black-gloved hands laid their contents on the stout 16th-century table by the fire. Bested by his own curiosity, Frankenstein found they were eclectic. Most were written in a nearly-illegible scrawl, but he could make out several highly-advanced anatomical models, biological surveys of the human body, as well as chemical analyses that rivalled the work of professors he had known. If this were truly Heron’s own work, then he was no fraud. Yet the papers were also interspersed with utter nonsense. Every third page seemed to be an alchemical treatise – and how was it that a man who must be at the very forefront of scientific knowledge could also waste himself on drivel like this? It was scarcely more than fanciful drawings of lions and dragons.

The lions and dragons were entirely too familiar, and Frankenstein recognized a shameful touch of excitement left from those old days before he had seen alchemy proven so conclusively wrong. Still worse was an impulse that whispered of how delicious it would be if Heron could overcome the triumph of reason over alchemy at long last. All that time spent with Henry poring over discredited books – but he caught himself. The man was clearly brilliant, but that was no excuse for Frankenstein to allow himself to indulge in such a fantastic rejection of reality.

Alchemy aside, it was a worthier effort than he could ever have hoped for. “This is impressive,” Frankenstein said, “I’ve never seen work like it.”

Dr. Heron carried himself with light steps to hover over Frankenstein’s shoulder, entirely too close. “Yes. Your experiments did prove useful to me as a basis for this next stage of my own work. That is why I’ve come to you and not some other equally capable surgeon.”

“You may need another surgeon still. I have no doubt you’re onto something, but I am retired, and for good reason. What you have here is the beginnings of an artificial man, and I have no intention of revisiting my own failures.”

“There will be no failure this time, Baron. From your mistakes come my successes. Because you were here before, I was able to correct for your errors. This will succeed.”

“It hardly matters. You’ve managed to intrigue me, I’ll admit, but I cannot make another man.”

“Not merely a man, Baron. That was your goal, it isn’t mine.”

“And you don’t know what it was like to watch my creature fail to become anything like a man.”

“Ah but you assume that humanity is a worthwhile goal. Perhaps it was for you, but my aim is not simply the human but the transcendent. It’s the potential to escape the limits of humanity, to reach into higher spheres of existence – there are possibilities here you wouldn’t dare to conceive.”

With black-gloved fingertips Dr. Heron picked superciliously through the papers, placing one page after the next before Frankenstein with a flourish. Each was a reproduction of one alchemical woodcut or another; kings and queens, swans and crows danced across the table.

“You must be joking, Dr. Heron. Alchemy is… it’s not only unscientific. On a fundamental level it’s incompatible with the entire idea of a mechanical universe. And like it or not, that is the reality we live in, the body most especially. It’s a machine built from parts – the heart to pump the blood, the liver to filter poisons. I really don’t see how you can hope to build a man at all if you can’t see how he’s made of his constituent parts.”

Heron tutted like a schoolmarm. “Perhaps I would be worried about that if I hadn’t already seen incredible success with my methods. What other explanation could you offer for the restoration of my own health, youth, and beauty? I am more than one hundred and twenty eight years old, you know. It is through alchemy and alchemy alone that I have given myself new life.”

“You cannot be serious.” There was nothing to corroborate this statement, aside from the uncanny atmosphere Dr. Heron carried about him. It wasn’t enough, though, to be merely strange.

“You must admit you are curious; it’s plain in your face. All you would be giving me is the use of your hands; the work itself would be my own. You would be able to observe, of course, but aside from assisting me in the surgery you may do as you wish.”

It was an awful temptation to see what would happen. After all these years shut up alone, merely the presence of the other man was an excitement. There were things moving in him which hadn’t awoken in so long Frankenstein had forgotten they existed, strange little hopes and half-dreamed desires whose eyes he couldn’t quite meet.

“Do you understand what you’re asking of me, to take up the knife again?” he asked, “Do you know what it did to me, when my creature killed those people?”

“Oh but Baron, for men like us there’s no room for regrets. If we had them, what would be left of us outside of them?”

Frankenstein had lost. He was simply too curious to turn Dr. Heron away. Worse, having no interest in travel himself and nowhere hospitable to send the man for miles around, he would have to give Heron room to stay. The manor was large enough for it, after all. If they kept to their respective wings he could avoid him for weeks, if need be.

The cellars were the most obvious place to put a laboratory. After all, there was nowhere else nearby to send Dr. Heron and he had most of the relevant equipment already. Some of it was a touch out of date, but it would do well enough. It brought a little more life into the house, he felt, to have work going on, and the electrical generator they installed could be heard even up to the rafters. Aside from being barred from use of the adjacent family crypt, Dr. Heron could have full run of the place. After all, Frankenstein planned to spend most of his time continuing his own research into organic chemistry.

And so it was that two months later Frankenstein found himself knee deep in mud shoveling up bones and filth. Heron was perched on a nearby gravestone, having pleaded mercy for his damaged hands. Frankenstein wasn’t given to this sort of work, sweating and aching as he pulled various remains out of the muck. He would have much preferred to contact the coroner’s office for the necessary parts, but he knew full well the sort of attention that request would bring attached to his name. With an annoyed groan he heaved a surprisingly fresh forearm out of the earth and held it up like a prize fish.

“No, not that one!” came Dr. Heron’s amused admonishment, “Here, bones – bones are what we need. Just the scaffolding, no flesh. You’ll get nowhere stitching together someone else’s used flesh.”

Frankenstein, panting with exertion, reared back to look the smaller man in the eye. “I thought -” he began.

“I know what you thought.” Heron hovered just over his left shoulder now, looking down into the pit. “It won’t be the same this time. I know your methods – mine are better.”

“Maybe I would believe you if I had any idea what we were doing.”

Heron grinned as if amused by how impossible he was being. “All will become apparent in time,” he said with a dismissive wave of the hand before stalking back to his seat on the tombstone.

“This is becoming ridiculous, Dr. Heron. Look at me! I’m exhausted and covered in filth – and why? You’ve strung me along for months now on little more than breadcrumbs, and I’ll admit I’ve allowed it, but if you don’t give me a clear idea of what it is we’re up to then perhaps I could find better uses for my cellars.”

“Get out of that hole,” Dr. Heron snapped, but offered him an arm to lever himself onto solid ground. Heron didn’t disguise his disgust at the mud left behind on his jacket sleeve. “It’s not simply a matter of finding the right parts and putting them together correctly. We are embarking on a process of creation – true creation from nothing. The bones will give us a frame to work around, but the rest of it will be entirely of our making. It’s not simply a matter of snapping together the right parts in the right order like children’s toys. Do you understand what I’m saying?”

“I don’t suppose I do.”

“You must throw off the limits of acceptable thought, Baron. Those small-minded fools at the university convinced you to abandon your curiosity because they couldn’t see past their own tiny realities. We are both already unthinkable to them. I know you haven’t forgotten what you saw in alchemy.”

“In concrete terms, please, Doctor.”

Heron sighed and with an alarmingly feminine flutter of his lashes said, “Once the frame is grown around the skeleton, we will go about adding the heart, the brain, and the other vital organs. Here -” he plucked something sodden and black from the open grave, “for the heart, we will take a small sample of this and allow it to weave itself around a hen’s egg. That way we can be certain the heart will be fresh and young. The liver can be nurtured in a cavity on the rocks of the shore, where it can be kept moist by the sea water. The lungs and most of the minor organs can be grown inside a still-living pig, provided we do some trimming to ensure they have room to grow. As for the brain… we’ll leave that for now. It will be last.”

Perhaps the reason he had neglected to spell out the details of his plan until now was because they were utterly mad. During the carriage ride back, both of them nestling bags full of bones in their laps, Frankenstein was filled with the urge to stop at the nearest town and leave Heron behind. He would have, were he not bored and lonely, or so he told himself. They really had gone beyond what was worthwhile to think about, but Frankenstein was a rather sad man, with little better to do than fritter his time away on nonsense. If he wasn’t so terribly lonely – but, ah, that wasn’t worth dwelling on.

Heron was the least hospitable person Frankenstein had ever lived with. He was insufferable at meals, barely picking at his food and drawing Frankenstein into conversations he’d really rather not have. He took no notice of Frankenstein’s needs to the point where even in a grand manor home he managed to constantly be in the way. Heron also had a gift for saying precisely the wrong thing at precisely the wrong moment and making one feel a bit stupid for not having anticipated it. Still, he was never, ever dull.

Frankenstein found himself bitterly disappointed to discover that in fact all of Heron’s ideas were scientifically sound. They began by mixing together the chemicals that make up the human body in a large tub and arranging the bones so that, when an electrical current was passed through the mixture, a body would shape itself around them. Even the hen’s-egg heart turned out to involve a somewhat complex chemical reaction, and the liver took advantage of several specific conditions only present in certain areas of the shore.

There was no accounting for his reaction, save that perhaps there was some part of him that wanted Dr. Heron to be a fraud. Where before Frankenstein had failed because he attempted the impossible, now he had to contend with having been wrong. Now he had to watch as another man did precisely what he could never manage.

The memories were no help. He could hardly stand to think of what his creature had done, but worse still were the thoughts of earlier times. Long days in the library picking through dusty tomes, seeking forbidden mysteries. He had friends in those days, and just the thought of them was more painful than he could bear. Every alchemical technique Dr. Heron used brought with it so much unwanted memory. Suns and moons and fire stirring up times safer left forgotten. Even now the smell of mercury and sulfur had him miles from himself.

“Sulfur and mercury,” Frankenstein murmured, leaning over the bone-strewn apparatus with his arms folded behind his back, “The wedding of the Red King and White Queen. I remember how this goes.”

“Yes,” Heron replied without looking at Frankenstein. He was busy screwing two bits of metal together. “I’m glad you’re beginning to come around.”

“I don’t understand how you managed to make alchemy work alongside science instead of against it. The philosophies are so different, one would think they couldn’t be reconciled.”

“What do you do when you want to make a new man of yourself? You go out and buy a new coat, perhaps you get a haircut or manicure, maybe you purchase a top hat. These things change your reality in the same way alchemy does.”

“Yes, between people. That’s how you communicate with people.”

Setting aside his tools, Dr. Heron smiled and laced his hands together. “Ah, my dear Frankenstein, what you don’t realize is that there is nothing out there but people. Horrifying, I know,” and before Frankenstein could cut in, he continued, “Besides, the alchemy shouldn’t matter much to you since the experiment is scientifically sound. There is some excess in the mixture but most of it will be burned off in the process.”

“Only most of it? Not all?”

“My aim isn’t to reproduce humanity but to improve on it. I have no intention of copying another man’s work, even if that man is God. I am an artist.”

And then taking back up the burette he was working with, Dr. Heron set about titrating blue liquid into an Erlenmeyer flask. Looking over the diagrams and figures and then back to their experiment, Frankenstein was filled with the terrible sense that what they were creating was so far from human it bordered on perversion. Looking at the mixture of bones and chemicals, the wire outlining the rough shape of a body, the diagrams which seemed to indicate something he scarcely dared to think about awoke in him such dread that he could not help but give it voice.

“It does seem a little odd… with the arrangement of the, ah, the organs,” he murmured.

“Odd? What’s odd about it?” came the distracted reply.

“How do you expect this thing you’re making to assimilate into society?”

Dr. Heron turned his long nose up at that. “How am I supposed to take that, coming from you? And how fares your creature, Baron Frankenstein?”

“How dare you?” Frankenstein snapped.

It was not the first time Heron had needled him like this – the man seemed constitutionally incapable of sincerity – but something in the phrasing brought with it a whisper of a new unbidden memory, unforced but quickly suppressed. Frankenstein was left with the hot anger of the recently disturbed, undercut by an uncanny sense of the familiar.

“Even after all this, do you really expect our creature to be like any other person?” Dr. Heron asked mildly, “Of course it won’t be, it will be better than any of them.”

“I don’t think you have the faintest idea what you’re talking about. You haven’t a clue why my project ended in disaster,” Frankenstein snapped.

Only a slight look of surprise crossed Dr. Heron’s face, a widened eye and raised brow, before it was wiped away into his usual mannered sense of superiority. “I’m sure it was very tragic. Now would you please hand me the vitriol?”

Frankenstein nearly ordered the man to leave his house on the spot, but some impulse stayed him. He stood rigid at the far side of the table, white-knuckled. Heron glanced at him briefly before returning to his titration with a soft sigh.

“I would not have chosen you to assist me if I didn’t think your experiment was the absolute best of its kind. If I am less than accommodating of criticism it is only in the same spirit I am certain you applied to your own efforts. Now, the vitriol, please. The timing here is critical.”

Handing Heron the vitriol, Frankenstein wondered at himself. Despite everything, he was still here. Heron was an awful little ghoul of a man, unfit for any kind of companionship, and yet Frankenstein was compelled. There was no question of his brilliance, of course, but brilliance alone could not account for what drew Frankenstein on.

“If you watch now you’ll see an impressive change in colouration,” came Dr. Heron’s distracted voice.

Frankenstein stepped closer. “I do remember a thing or two about this as well. Vitriol and sulfur, isn’t it? They call it the green lion devouring the Sun. It’s to ritually purify the material, to create the conditions for the divine spark of life.”

“Ah yes, well, you were always so dedicated to your studies in that area,” said Dr. Heron, his attention firmly on the burette. “I remember it caused a minor scandal when they let you into the university with alchemy as your only background.”

Far from the hot anger he felt before, something cold and wary now yawned in Frankenstein. At that moment, he was certain he had been right about knowing Heron, and that, more importantly, Heron knew him. There were things the man was hiding from him deliberately; it wasn’t simply a matter of social negligence.

“Who are you?” he hissed.

“Hm?”

“We’ve obviously met before, don’t deny it.”

“My dear Frankenstein, it’s hardly something to concern yourself over. We met once or twice in passing at the salons, I hardly think you’ll remember me.”

“Then it shouldn’t be a problem to tell me who you are.”

Heron put down his tools and considered Frankenstein a moment. Then, inclining his head, he said with some delicacy, “I was Professor Somerset.”

It took Frankenstein a moment to remember who Somerset was, he knew the man so little. Even then all he could summon was the image of an especially wizened old intellectual, wheelchair-bound, who had appeared once or twice in the background of more important events. But more than that, he remembered Professor Somerset’s funeral.

“Professor Somerset is dead.”

A devilish smile lit Dr. Heron’s face. “Of course. You don’t think I could have showed up at the university eighty years younger and had everyone welcome me with open arms, do you?”

Frankenstein was unsure whether he was more disappointed or disturbed.

“That can’t be right, sir. Professor Somerset, a secret alchemist? The man I remember spent twenty years studying the mating habits of sandpipers.”

If his suspicion caused Dr. Heron any concern, it certainly didn’t show on his face. “Well yes, but you assume that was my first lifetime. I’ve been at this quite a lot longer than you would expect. There’s an unbroken line of us dating back well into the 1400s. I’ve seen a great deal in my time.”

On its face it was a blatant lie, and yet even the mere suggestion that Heron had known Frankenstein when he was that young, before he had learned to school his own affect and suit it to proper society, chilled him more than he dared to contemplate. In fact it made him quite disinclined to investigate further. The thought that he might uncover more of his own youthful embarrassments made him faintly ill.

It came too easily, with too much smugness for it to be a lie the whole way through. Perhaps Dr. Heron hadn’t been Somerset, but it was close in some way to the truth. The suggestion that Heron was more than he seemed appealed to Frankenstein more than he wanted to admit, excited him, awoke his imagination. Heron could never know how badly he wanted it to be true, for him to truly be one of the alchemists of old, to have discovered the secret of immortality. But it didn’t bear thinking about, really, truly, it didn’t bear thinking about.

The work advanced quickly from there. In a few weeks, tough, fibrous bands ringed the hen’s egg, trembling just on the edge of pulsation. The pig as well was progressing rapidly, but that meant regular ‘pruning’ to ensure enough room for its new organs. Dr. Heron, of course, begged his damaged hands, and so the wretched task fell to Frankenstein once again.

He was too curious to risk damaging their rapport, too curious to see if he could dig information out of Heron about his past. His successes were few and far between; in fact the more direct he was, the more vague Heron’s answers. It infuriated him, and that only fed his curiosity. He became quite obsessed, staying up into the wee hours of the night to dig through the family library in hopes of catching some glimpse of familiarity in the lives of Paracelsus and John Dee. When Dr. Heron inquired after his lost sleep, Frankenstein replied it was background research for their experiment, which pleased Heron.

Dr. Heron seemed to relax a little around Frankenstein after that, assured that Frankenstein was convinced of the truth of his expertise now. It wasn’t abnormal for him to lean dramatically against a bookshelf, waving one hand as if he were playing to an audience while he lectured Frankenstein on some obscure point or another. Frankenstein would arrange himself to look as if he was only half listening while he leafed through his notes, but in truth he was rapt, listening for the slightest hint that might assist him to solve the mystery of who Heron was.

“The heart responds well to electrical stimulation,” Heron said one night, then paused, gazing at Frankenstein with curiosity, “Now, what do you suppose would happen if I ran a current through your chest.”

“I would die?” responded Frankenstein, not looking up from his book.

“Yes, yes, of course you would die. That’s irrelevant. What matters is the role electricity can play in purification. The old alchemists used fire, as I’m sure you’re aware, but fire is a blunt instrument. Electricity is capable of much finer control. It is less tied to base materials than fire, and so it is purer.”

Dr. Heron had a tragic delicacy about him that Frankenstein found utterly compelling to watch, but in that moment all Frankenstein could think was that nothing he was saying mattered at all. He often did this, expounding on subjects in what almost felt like free association. For once, Frankenstein was tired of him.

“Where do you learn these things?” Frankenstein asked.

Heron sniffed. “My dear Frankenstein, I do need to keep some of my secrets.”

“As your patron I would be much obliged if you could give me some proof of the things you say, at least some of the time.”

“Is that what you are? My patron?”

“Your landlord?”

“Well I am feeling somewhat patronized,” Dr. Heron huffed.

“I don’t have any doubts as to your ability,” Frankenstein said, doubting himself all the while, “But you must understand how much it would reassure me to have something to corroborate the things you have to say. You must have studied somewhere, made publications, or collaborated with someone. You can’t have worked in total secrecy your entire life.”

“You would be surprised how much can be done when one is free of outside entanglements.”

“That doesn’t answer my question.”

Heron was pacing now. “If you really desire proof of my faith in my abilities, you need look no further than the brain of our creature.”

This threw Frankenstein for a moment. Their plans for the creature’s brain hadn’t come up in weeks. “You’ve only given me the broadest hints as to what that might be,” he said.

The pacing increased, like a panther too small for his enclosure. “The brain we will be using is my own.”

Frankenstein closed his notebook. He didn’t like this. It was worse than if Heron had dodged the question entirely. “I thought you said you had already extended your life with alchemy, fixed your health.”

“Oh I have, but this body is only a first iteration. It can be improved upon still.” Heron waved his hands as he spoke, no doubt in agitation, but there was still a strange, jerky charisma that held Frankenstein’s eye.

Frankenstein allowed himself a long moment to look at Dr. Heron. He was always watching him from the corner of his eye, darting glances, never fully and directly where Heron could see him. What it was about the man he could not say, but he could see it in him, something greater-than-human. It wasn’t the performance he was putting on, no, there was something there threatening to escape. If he wanted to break free of the limits of humanity, he need only push a little, just a little, he was nearly there. Was it really transcendence he was seeking, or self-destruction?

“You’ll lose yourself,” said Frankenstein.

“Do you think I enjoy relying on your hands instead of my own?” Heron snapped, holding out his black-gloved hands for inspection.

A hot flush of embarrassment ran through him and Frankenstein dropped his voice. “Then what is it you plan to do afterwards, once you’re in this new body of yours? What sort of life will you make for yourself?”

Heron puffed up like a haughty bird. “Well I’m not planning on parading myself around the scientific convention circuit if that’s what you’re asking. I know what you’re thinking, and I have no intention of making a traveling freak show of myself. In any case, I thought you were here for the thrill of the venture, not the accolades.”

The look Frankenstein gave him was funereal. “You would really stake your life on this experiment.”

“I’m sure you would have done the same with your own.”

It was beyond him to continue. That evening all Frankenstein could think of was destroying the experiment. It had a face now, a horrible, blank thing like a cheap mask. He tried to picture Heron’s spark animating its features and found it impossible. It would be nothing to shatter it with a blow, for it was empty inside. They had not yet inserted the eyes, the tongue, or the brain.

Yet he couldn’t bring himself to destroy it. It wasn’t that Frankenstein felt anything for the creature – what was there to feel? No, he simply couldn’t stand to ruin so many months’ work.

Time was no longer on his side, however. With the creature so close to completion, there wouldn’t be long to put off the issue of the brain. The fight, which was inevitable, would be ugly, ruinous even. What would he do then? Frankenstein was as desperate as he had ever been to solve his little mystery, and surely it would be impossible to get anything from Dr. Heron after that. Worse still, the man might leave.

He could delay it. In fact, it was vital he did so. He had avenues he hadn’t yet explored, had hardly dared to think of, and he couldn’t possibly let things end before he had a chance to delve deeper. The university had answers for him. Dr. Heron had met him there, Frankenstein was sure of it. There must be something to be found if he retraced his own steps.

There was nothing Dr. Heron could do without him, not at this stage. He needed Frankenstein’s hands, after all, so he would have no choice but to wait. It had been so long since Frankenstein had left home, he had nearly forgotten the rest of the world, and when he rode out the next morning the sight of the mountains and forests shocked twelve years of dust out of him. But Frankenstein did not care to think long on mountains any more, and the feeling passed.

Ingolstadt was not a large town, university aside, but to Frankenstein it roared and heaved with traffic. With every step he watched for eyes on him, waiting for an arm to catch his or for a harsh voice to call out. He hadn’t simply left, he had been chased. Even the main promenade was a tour of his personal terrors. Here was the corner where he and Henry had collapsed in drunken laughter, it couldn’t have been more than two weeks they’d been at the school; there was the alley where his creature had raised a little girl above its head before falling to a shot in the arm.

The library would be his first destination. He would give Professor Somerset’s records a fair glance, but his real object was the archives, where they stored the old records of alchemical research. No one troubled him, nor spared him so much as a second glance, but the sight of the old place filled him with an unaccountable terror.

The librarian barely looked up at him before saying, “Records on the third and fourth floors are accessible to students and staff only.”

Expecting the worst, Frankenstein said in a brittle voice, “I’m looking for the body of work left behind by Professor Somerset.”

Now she met his eye, asking, “Are you a student?”

In that moment he was envious of how little Dr. Heron cared about how people thought of him, because all he could do was stiffen further and say, “yes.”

No request for proof of identification was forthcoming. She only glanced back down at her work and replied, “Third floor, to the right and back.”

Frankenstein had been forgotten. The shock was slow to come. No one had recognized him. Had he aged so badly, or were his crimes merely so irrelevant now that no one cared to wonder? All his years of hiding, had they been a waste? How long had he been able to return?

The collection of Somerset’s writings was useless, worse than useless; it was entirely about sandpipers! What more could he have expected? Frankenstein cursed himself, he cursed the entire venture. He thought of Henry, whether he could have written to him, whether he had simply gone wrong these last ten years. But he couldn’t afford to distract himself. He was, after all, working on borrowed time. Dr. Heron was waiting for him.

If he wasn’t Somerset, perhaps Frankenstein’s suspicions were right. Heron could be anyone, he could be Paracelsus himself! And why not? All things seemed possible now, and it accounted for the Somerset lie. If Frankenstein had managed to hide himself so well, then why could Dr. Heron not have done the same? He said he had rejuvenated himself. Perhaps he had been too ancient or disfigured to show his face before. Perhaps he had lived under the floors or behind the walls, somewhere hidden away from the world where he was able to look in on it.

The alchemical records had always been Frankenstein’s object anyway. Dr. Heron must have worked with them as well, how could he not have? He might have been there when Frankenstein had been conducting his own investigations. But the moment he walked down those ancient stairs Frankenstein was assailed by memories. That particular scent of dust ran back the years and for a moment it was as if he could round a bend in the hall and there would be Henry, nose in a book, smiling and waving Frankenstein down to chatter about his latest discoveries. Something hollow and aching cut into him. How badly he missed it! How badly he wished to go back, to be able to forget this decade of dreariness and find himself again among friends, in a world where it still felt like things were possible. What they could have done together! What they could have made of themselves! If he could only have fixed his mistakes enough to keep Henry by his side, then, ah – the sight of those decrepit armchairs, stuffing long since flattened, nearly brought Frankenstein to tears.

Nobody ever came down here; it had only been the two of them. Oh yes, scullery maids, kitchen drudges, and washerwomen used the service corridors nearby, but there was no way Dr. Heron would have happened upon them in the archives by chance. Frankenstein’s hands shook as he leafed through the old books. It was too much, too close, the old ways of thinking resurfacing, the idealism all the more painful for knowing the harsher truths of reality.

Suddenly Frankenstein found the archives smothering. He couldn’t stay here. There would be nothing gained from rereading the same old books over again. He must go out, up and out into the world. They had forgotten his face, after all. There was no reason to hide.

Frankenstein toured the neighbourhoods where they used to hold the old salons, but unlike the archives, ten years had made them foreign to him. The parties he had known were long over, replaced by whatever was fashionable now. Even the houses were different. He could stay here, he realized. The world had moved on.

Passing old Frau DuChamp’s house, he remembered with a shudder the party where the rector’s daughter had dropped herself into his lap and tried to hand-feed him canapés, laughing like it was a joke he never fully understood. Henry had never come to the salons, kept himself to alchemy even when Frankenstein had realized how much the practice was frowned upon. They saw each other less often by then. Had Heron been there? He claimed to be, and there were so many faces that passed through the salons that Frankenstein would never have noticed another.

After that he had begun work on his creature. He could walk to the remains of the shed out on the edge of town, though he had no intention to do so. It was to have been his crowning achievement, his proof to the professors that he was not only worthy but brilliant. He had been so tired of the disrespect, the disapproving glances.

There was no one else there by then, not Henry, not Heron, no one in that shed but himself and his man-made man. For months his life had dwindled to nothing but that work. Henry had spit in his face, and he was right. The long hours he spent with his hands caked in dried blood, those were for him alone. It had been a cold year, and with the windows open for ventilation the insides of his creature steamed. It had stunk of hog fat. Thank God the place had burned down, thank god. He would never go back there.

Frankenstein hardly dared to let his thoughts drift toward what had happened after that. The beautiful body he had tried to construct, his greatest of men, had never become a man at all. The intricate play of the muscles and ligaments turned horrible, repulsive once it was in motion. Everything about it had been wrong, from its stumbling gait to its dead, empty gaze. To think he had tried for beauty! For grace!

He shouldn’t have come here. There he stood, empty handed, without even the smallest shred of evidence as to who Heron was, and the thought of the thing waiting for him back home made him ill. He wanted to flee, to run to France or Italy or Spain, where no one knew his name, but that would mean leaving it in his house. It would sit there, waiting forever for him, if he did that. No, Frankenstein had to go back, he had to destroy it. Then he could leave, go where he wished, he could even bring Heron with him. Surely he’d be saving Heron as well.

The trip back home was far less leisurely than his one out, and by nightfall Frankenstein was passing through the gates of his manor. There was no time to waste, after all. The thing had to be destroyed; the longer it was left the more its malign influence would seep into every crevice of his home. It should be simple enough to sabotage; all he needed to do was to reactivate the electrical current and increase it until it cooked the flesh ever so slightly. It would be totally invisible to the naked eye. The creature would simply, silently die.

Frankenstein slipped in through a side door and made directly for the basement laboratory. It was late enough in the evening that Heron was likely taking a night-cap up in the library, so he was unlikely to be disturbed. He would need an excuse, though, if Heron were to come down. The man would hate him if he knew what Frankenstein was doing, and Frankenstein couldn’t withstand that now. The generator made an awful racket. But he could tell him it was enthusiasm, that he could hardly wait to see the creature before coming to say hello.

Oh what a wretched noise the thing made! It was louder than he remembered, like a pack of vicious wolves. Hearing footsteps above the roar would be impossible, so fighting against his own racing heart Frankenstein increased the current as quickly as he could. The scent of burning flesh filled the room. The body, prone on the slab, twitched and danced as the current forced muscle contractions out of it.

Enough, it was enough. He flipped the master switch and the silence rushing into the room left his ears ringing. Whatever spirit had driven him all the way back here from Ingolstadt abandoned him at once. Frankenstein sagged against a wall. He hadn’t thought past this point. What was he to do from here? He could humour Heron for a time, but the man would obviously discover the creature was dead. Then what would he do?

“You’re back,” came Heron’s voice. Frankenstein jolted to attention.

“Oh yes,” he said, brushing his hair back and adopting an air of what he hoped was casual authority, “I had meant to say hello but I couldn’t resist looking in on the work.”

“And how was your solicitor?” Heron asked, slinking across the room, “Did you manage to close your business?”

Frankenstein felt sweat prick the back of his neck. “Uneventful, really.”

“Then I take it you are ready to continue with our experiment tonight.”

“So soon? I’ve only just arrived and I’m tired from the journey. I’d hoped we had time to catch up.”

“But here you are in the laboratory with the generator running. You must be eager to begin our final preparations.”

“Yes, very eager.”

A smile lit Heron’s face which only the Devil’s could rival. “Good. We must waste no time, then. After all, you’ve already left me waiting a week. Any longer and it will begin to deteriorate.”

“Must it be tonight?” Frankenstein groaned out.

Heron shrugged. “And why not? All that’s left is to transfer the brain.”

And then, deliberately, he caught Frankenstein’s eye and held it. Frankenstein was filled with the terrible sensation that the man knew every thought in his head, knew precisely what he had done and that his only aim now was to torture him for his error. But no, no that made no sense. Heron was needling him because he knew Franknestein didn’t want to operate on the brain.

“We’ll – we’ll go back to the graveyard,” said Frankenstein, “Find one recently dead. Or the local coroner’s. I can’t – “

“Oh but you must.”

“No, no,” Frankenstein stammered, “To transfer your brain – your brain… if I ruined the most brilliant mind in Europe, it would destroy me.”

Heron’s eyes raked him. He looked softly amused, a touch tired. From his pocket, Heron took a small case and from it plucked a single white pill. Still meeting Frankenstein’s eye he placed it on his tongue and swallowed.

“I’ve taken the decision out of your hands,” he announced, “I knew you wouldn’t be willing to go through with it on your own, so I took some precautions. It’s quite deadly, you know. You have forty five minutes, perhaps an hour to remove my brain; otherwise I will die.”

A sick lightheadedness took Frankenstein, as if the world was sliding out from under his feet. Doom, it was doom.

“Why? My god, why would you do something like that?”

Heron looked weary now. When he spoke he was quieter, calmer than before, as if some manic impulse had abandoned him. With perfect serenity he flexed his black-gloved fingers. “Life in this wretched, ruined body is no life at all. Every day is agony to me, do you understand that?”

“And you’ll throw your life away for that? For that?” Frankenstein gestured towards the corpse, “That dime store mannequin stuffed with pigs’ guts?”

For the first time. Heron looked away from him. “We have all we have on this finite earth, and if we hope to reach beyond that, to find the sublime, the transcendent, we must be able to escape the confines of what is given to us. There are joys that can never be experienced without reaching for the chance to become more.” And then looking back to Frankenstein he summoned fire into his eyes, “We’re nearly there, Victor. The alchemical masterwork!”

Frankenstein could contain himself no longer. “Alchemy isn’t real!” he cried.

“Don’t you think I know that?” Heron hissed, scowling now, “Of course alchemy isn’t real. But you – you wanted it to be, and I needed you. Did you like the little show I put on for you? You must have. You’re still here, aren’t you?”

Shaking, Frankenstein felt as if he’d been slapped. Heron had never believed in it. It had merely been an act for his benefit. Good god, and he had let himself be strung along! “You didn’t need to,” he began

“Oh didn’t I?” Heron interrupted, imperious, “You, who were so determined to stay hidden from the world. Oh, you would never have helped me. You would have turned me out to the storm if I hadn’t caught your eye with something shiny.”

He had killed him. Frankenstein was looking at a dead man, and it was his fault. “I can still save you, synthesize an antidote.”

“Half an hour now.”

It would be worse than impossible to put Heron’s brain in the creature, but perhaps he could preserve it. He could find a jar, a bath, something and keep it safe until he found some way to save it. It wouldn’t survive where it was now.

“Alright,” he said, “Let me get prepared.”

The only sound in the lab was the clinking of metal and glass as Frankenstein sterilized his surgical equipment. The conditions were less than ideal, he thought. He wanted to have done this properly, taken the time to ensure a safe operating chamber. His hands were still shaking. He could nearly feel the dead weight of Heron’s brain in his hand, an inert, lifeless lump of flesh.

Then came a cry, “It’s dead!”

“What?” Frankenstein sputtered.

Whirling in rage, Heron’s face was pale white and convulsing, his skin taut to the bone. He had never looked more ghoulish. “What did you do?” he howled, “You’ve ruined me!”

Crossing the room in a stride, Heron rifled through the medical equipment with little regard for his own safety. Frankenstein could only stand and watch, struck dumb by his own terror, until Heron was raising a knife above the corpse of their creation. From some inexplicable urge, Frankenstein found himself shouting and throwing himself upon the other man, desperate to wrest the knife from his hands. Why he felt so desperate to save a lifeless shell, Frankenstein could not say. The thought of that knife cutting through the desiccated flesh horrified him beyond words.

Someone’s blood spattered the corpse. He wasn’t sure whose. The knife clattered to the ground. Heron, hysterical, fell on himself in wild uncontrolled laughter.

“Are you happy, then, Victor Frankenstein?” he rasped, “Are you happy? Do you think you’ve figured it out? That there’s some secret you’ve found that means you understand things better than I do? I wasn’t lying when I said your experiment wasn’t the only one of its kind, or are you so arrogant you thought nobody could manage it better?”

With that, Heron ripped off one of his gloves and threw it to the ground. His hand was blackened with gangrene, held together by stitching so crude and rotten that it had begun to unravel, the flesh threadbare. Still laughing, he pulled up the sleeve of his coat to reveal a patchwork of fleshes, waving his arm at Frankenstein as if reaching to grasp something.

“Are you not disgusted? It was your technique I used!”

The blood on the corpse sizzled and a red glow began to fill the room. Both of them looked to the slab, which was now emitting red light. Before either of them could react, the glow gave way to searing light, and Frankenstein hunched, shielding his eyes. It was as if the final judgement had come and the whole room given way to the purifying fire of heaven.

Frankenstein remembered what Heron had said about electricity, though it felt like it was in another life, about purification. And the blood, the blood must have done it, to tip it into the final stage of the alchemical masterwork. The rubedo, the reddening, was depicted with blood. The dueling natures of the world, the red king and white queen, marry and become one.

He knew it, all along he had known it was real. All of it, all of it was real. There would be no boundaries any more, no limits. They had done it; they were free.

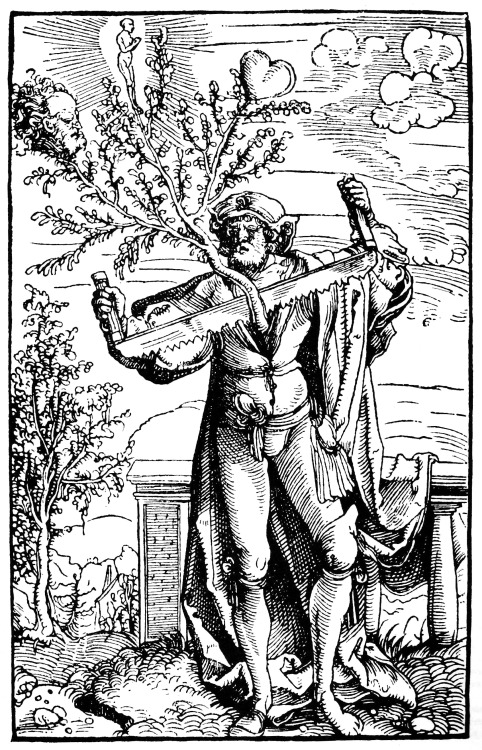

Slowly the light dimmed, until finally Frankenstein could see again. There in the room stood a new figure, unmistakable to someone who had learned as much and deeply as he had. A holy thing: the Divine Hermaphrodite. Dual-headed, one face a man’s, the other a woman’s, winged, and with the aspects of both sexes, it was hard to look at directly, too beautiful for mortal eyes and far above either of them. It did not move, standing in the middle of the room, but the air tasted sweeter and it felt as if the walls had fallen away.

There, not too far from Frankenstein, was Heron, still cowering against the wall in abject terror. Anger warred with pity in his breast. Frankenstein was filled with some unaccountable urge to protect Heron, but from what? And now, looking again at their creation, he found himself terrified. It was too much to exist, impossible in its majesty, closer to god than man. It looked at him. He wished he could run, but still he felt the urge to throw himself between it and Heron, to keep him safe from it. He hated himself for the feeling, hated Heron for awakening it in him, and hated him for tricking him into believing again, and still more for its being real.

Nearly blind with fear, Frankenstein picked up the knife.